When you picture a bee, the honey bee with black and yellow stripes may come to mind. A social insect introduced to the North American continent in the 17th century, the honey bee is often kept for honey and for pollinating food crops. We’ve heard a lot about honey bees in the news due to the risk of colony collapse and the agricultural impacts it could have. However, honey bee research overshadows attempts to identify and analyze the numerous native bee species living in the wild. One scientist working to close the knowledge gap is ecologist and environmental data journalist Joan Meiners. I interviewed her to understand the significance of her work, the daily life of a bee researcher and her role as a woman in STEM.

Meiners recently published a research paper on the native bee biodiversity in Pinnacles National Park, about 40 miles east of Carmel in California. Following up on a previous survey of the region, she and her colleagues wanted to sample the area to monitor the level of native bee biodiversity. Compared to honey bees, native bees live more solitary lifestyles and have more selective habits when it comes to pollination.

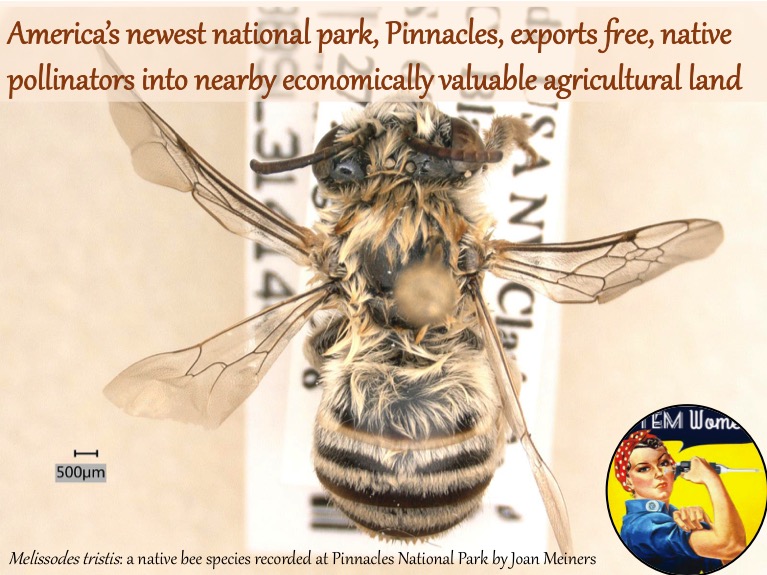

Meiners and her team took pleasure in the process of identifying about 50,000 different bee specimens. “Bees are beautiful and fun to identify. They can be metallic blue, bright green, have little mohawks of hair on their heads or interesting ridges on their exoskeletons.” Even the delicate patterns of the wing veins provide species variation clues. In total, she and her colleagues found 450 different bee species in the surveyed region.

And while this number seems impressive upon first glance, Meiners pointed out that there are relatively few studies available for comparison, citing just 23 similarly extensive surveys in the entire United States. She emphasized that Pinnacles National Park is the only area where scientists have surveyed native bee populations over multiple decades, allowing scientists to better track trends over time. “Without repeated sampling, what we know about wild bee decline is complicated by all this natural fluctuation and actually pretty restricted to agricultural areas, where we know they don’t really live.” In short, Meiners would like to see more native bee research done in the future.

Meiners’ research not only helps to advance our knowledge about native bee populations in Pinnacles National Park, but it also lays the foundation for further research. “In the paper, I really tried to highlight this point that more studies like ours are needed to really understand the value of natural habitats (before they’re gone) and the status of native bee decline”. By researching native bees with their uniquely interdependent relationship with plants, scientists can gain insight into the overall ecological health of a region.

Photo courtesy of Joan Meiners.

Wild, native bees are key ecosystem service providers in both natural and agricultural landscapes. Compared to the unstable European honey bee, on which United States agriculture is heavily dependent, little is known about the four thousand North American species of native bees…

Meiners et al. (2019) Plos ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207566

But how is this done in practice? As part of her routine, Meiners collects bees by laying colorful “bee bowls” filled with soapy water that attract the bees and preserving them in ethanol. Otherwise, she catches them in a net and then transports them in vials. For this, she roams through a specific sampling area each day. Rather than spotting them by eye, Meiners usually listens carefully to her surroundings to find bees: “You learn to be able to differentiate the flight patterns and the sound of a bee versus a fly versus a wasp flying.” By now, she has become so attuned to identifying different insects this way that her ears remain alert off the clock.

Once she collects the bees from nature, Meiners takes them back to the lab to be pinned and labelled. She’ll store the bees in climate-controlled boxes to prevent beetles from eating their specimens. Meiners explained that in order to identify bees under a microscope, they must be killed. The samples they collect, however, do not make a significant dent in the overall population of the many native bee species, most of which only live as adults for about a month.

Of course, I wanted to know how many times she had been stung. Her response surprised me: “The answer is five, though I’ve collected and handled at least 10,000 bees. It’s only five because native bees aren’t as aggressive as honey bees. Most of the species are solitary or less social than honey bees, so they aren’t guarding a hive and have less reason to want to sting you to protect it.” These five stings were typically encounters with unseen bees in the net.

Meiners’ interest in bees began in eighth grade, when she wrote a research paper on honey bees and won third place in the Colorado state science fair for a related experiment. Encouraged by her teacher, a female scientist, this early success sparked a lifelong vocation as a scientist. She later attended Mount Holyoke College, the first institution of higher education for women in the U.S. and she considers its all-female campus a factor that contributes to her success. “It’s about prioritizing women and education,” Meiners said. Namely, she didn’t learn to “let men speak first or dominate the conversation,” and she left university feeling empowered in the workforce. “I don’t let anyone tell me to be quiet about things I think are important.”

Joan Meiners’ educational background and career is not limited to bees, either. She majored in neuroscience and worked at a coastal ecology lab to research sea turtles and crab ecology, followed by research on the Canada Lynx in Colorado. She also works hard to bring science issues into the public sphere in her role as an environmental data journalist: “[I]f you stop spending time on a project once it’s published in the academic literature, it often never achieves its potential or metamorphoses into any policy changes.” Her goal is to get more projects that would normally be locked up in the “ivory tower” pushed through to the public sphere. She feels that by accurately gauging audiences, journalists can expose more scientific research, not just “flashy” research, so it sees the light of day outside of academia.

About the author: Erica Eller is a freelance writer and editor focusing on sustainability and conservation. Originally from the US, she currently lives in Istanbul. Website: https://ericaeller.com, Twitter: @ericaeller